Let’s start with the basics. It’s a matter of language… butter versus curd.

“In simple terms butter is an edible fatty solid made from cream and milk by the process of churning.” In fact, it’s quite fatty, containing at least 80% butterfat by current industry standards. By contrast, “curd is a soft, white substance formed when milk coagulates” either because it has soured or been treated with enzymes. This coagulated milk is “used as the basis for cheese.”[i] Just for the record, and with the following rhyme in mind,

Little Miss Muffet

Sat on a tuffet,

Eating her curds and whey…,

whey is the liquid that’s left after milk has curdled and been strained in the cheese-making process.[ii]

So much for the basics!

Butter and curd are decidedly not the same thing. And certainly no self-respecting cook or host would substitute one for the other at table! But as obvious as the distinction might seem, the difference between butter and curd is not clear… at least if you read the Bible. In fact, one edition of the Bible uses the word butter while another uses the term curd.

I’m not sure how I started down this path but it began in earnest when I consulted a Concordance, an index of principal terms found in the Bible. My Concordance, a wonderful leather-bound volume that I found years ago at a yard sale, was published in 1845. In it butter has a comparatively impressive presence with no less than ten Old Testament passages cited. With these citations in hand, I began leafing through different editions of this incredible text. It took only moments to discover that I was confronting a challenge. I couldn’t find any of the cited references to “butter” in either the Revised Standard Version of the Catholic Holy Bible or in the Holy Scriptures published by The Jewish Publication Society of America in 1966. In its stead was the word “curd.” Curious and undaunted by this language substitution, I next turned to The Authorized King James Version of the Bible published by Oxford University Press in 1944. In this edition of Holy Scripture the word “butter” did, in fact, appear. Moreover, it did so precisely as my Concordance of 1845 had noted. What’s this all about? An attempt at an explanation is, I think, required.

——– butter churns & firkins used for storage

Before considering this and several of the passages in question, it is, I think, worth mentioning that my Concordance indexed “curd” only once. The passage itself, Job 10:10, doesn’t use the noun curd but rather the verb “curdled.” Notably, all three of the editions of the Bible that I consulted – the Catholic Holy Bible, the Holy Scriptures published by The Jewish Publication Society and the King James Bible – used the same word: “curd”. Here, there are no butter substitutions!

Remember that Thou hast made me of clay [says Job];

And wilt Thou not turn me to dust again?

Didst Thou not [also] pour me out like milk and curdle me like cheese?[iii]

——- History of Job, manuscript illumination, Bibliotheque nationale de France, Department des manuscripts, Latin 15675, folio 5v.

There are two possible ways to read this. One takes into consideration the idiomatic meaning of “to curdle,” as in ‘it made my blood curdle with fear and terror.’ Let’s face it, the “sore boils” that blistered Job’s body from head to toe can be understood as disfigurements that resembled lumps of soured milk that would cause anyone’s blood to curdle with horror!

The second possibility is far more palatable but it also calls for thinking creatively. On the one hand, it requires that we visualize in our mind’s eye what curd looks like. (Think cottage cheese!!!) On the other, it asks us to imagine what butter looks like after it has been shaped and molded in wondrous ways.

For centuries, butter has been a medium for sculpture. Bartolomeo Scappi, for example, made note in 1571 of several butter sculptures featured at a banquet, including “an elephant with a castle on its back” (a personal favorite) and “a unicorn that has its horn in the mouth of a serpent.”[iv]

In more recent history, Caroline Shaw Brooks (1840-1913), the enterprising wife of an Arkansas farmer, produced the greatly celebrated butter sculpture Dreaming Iolanthe, 1873.[v] With that in mind, consider the single biblical reference to curd. To me, it can be read as anticipating the later use of butter as a medium of sculpture. In Job 10:10, God is characterized as a sculptor. Not only is He the creator of Adam and Eve, having modeled both of clay (Genesis 2: 27), He is also cast as a sculptor (if you will) for here he gives shape to poor Job’s face and body by “curdling” it with soured milk!

As for Caroline Brooks, she was by no means the first sculptor to use butter as a material suited to the art of modeling. Horatio Greenough (1805-1852), the artist responsible for the marble statue of a toga-clad and very oratorical George Washington (1832), was said to have displayed his craft of butter sculpting before a coterie of ladies enjoying tea with his mother. Antonio Canova (1757-1822), the master famed for, among other works, a recumbent and suggestively [un]covered statue of Pauline Borghese (1805-08), also was said to have sculpted butter. Working as a lowly scullery boy, he molded a lion that won him some serious financial backing.[vi]

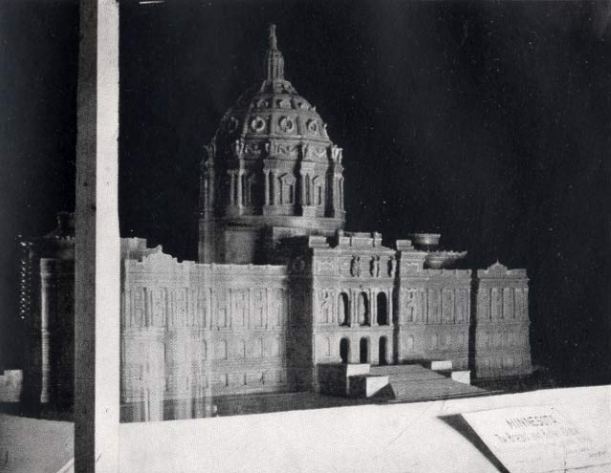

—– Minnesota State Capitol modeled of butter

The stories about Greenough and Canova may belong to the world of myth and conceit but Brooks was the real deal. Instead of wielding a hammer and chisel she shaped and etched figures with butter paddles, cedar sticks, broom straws, and a camel’s hair pencil! Clearly, she was in the vanguard. More than two decades after Brooks’ Dreaming Iolanthe garnered critical acclaim, butter sculpture began to come into its own in the arena of the fair, if not in the world of art. Among the featured exhibits at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York in 1901, was a rendering in butter of Minnesota’s State Capitol. Measuring over eleven feet in length and five feet in height, the work had kept John K. Daniels and his brother Hacon Daniels busy for at least fifteen hours a day, every day for more than five weeks. A fitting, albeit ephemeral, tribute to the “bread & butter state,” Minnesota, which sponsored the Exposition project![vii]

But back to butter versus curd.

I will settle the issue of terminology with Pliny the Elder’s first century, encyclopedic compendium concerning “the nature of things,” The Natural History. Butter, or butyrum in Latin and βούτυρον in Greek, means quite simply “cow cheese.” Let’s now face facts. “Cow cheese” is precisely the stuff of curd and butter so let’s go with butter as the catch-all term.

Pliny did more than supply us with a working definition of butter. He addressed the issue of its consumption. Butter, he informs us, is “held as the most delicate of food among barbarous nations, and one which distinguishes the wealthy from the multitude at large.”[viii] Writing several decades before Pliny, Strabo put a different spin on butter-eaters. Mysians, who dwelled in ancient northwest Asia Minor, or Anatolia (present day Turkey), abstained from eating meat, preferring to live on honey, milk and cheese. Perhaps because they shunned slaughter, they lived, according to Strabo, “a peaceable life, and for this reason are called… god-fearing.”[ix] Here, Strabo implies that there is something righteous about milk-products, including cow-cheese or curd or butter. So, too, do many of the biblical references noted in my Concordance.

In Genesis 18: 8, for example, butter is one of the comestibles that the God-fearing, devout, and virtuous Abraham set before the angelic strangers who visited him just before the destruction of the sin-ridden city of Sodom. The significance of the meal offered by Abraham is explained in, among other places, Deuteronomy 32: 13-14. Here butter joins honey as well as the “finest of wheat” and “the blood of grape” (wine) as the food that God bestows upon the righteous. No wonder then that in Isaiah 7: 14-15, a passage understood as foretelling the coming of Christ, we read the following.

“Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign.

Behold a young woman shall conceive and bear a son

and shall call him Immanuel.

He shall eat butter and honey when he knows how to refuse the evil and choose the good.”

I don’t want to push the equation of butter and godliness too far. Neither do I want to suggest that keeping idle – female – hands busy with the butter churn was a way to keep the fairer sex out of the proverbial playground of the devil. That’s me reading into a text! The truth is that butter, or at least the task of churning milk into butter, had its fair share of devilish overtones and undercurrents. Popular imagination saw pixies in the cream! Hence, for centuries, churners chanted charms when cream proved slow to clot. They did so with the hope of countering any and all spirits that might hinder their labor.

“Come, butter, come,

Come, butter, come;

Peter stands at the gate

Waiting for a butter cake.

Come, butter, come.”

According to Iona and Peter Opie, the editors of The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes, there is more than a little evidence to suggest chanting while churning was a widespread and long-lived practice. “Supernatural aid has been consistently called upon through more than 400 years of Protestantism. Thomas Ady, writing in 1656, knew an old woman who said the butter would come straight away if it [“butter, come, butter”] was repeated three times, ‘for it was taught [to] my Mother by a learned Church-man in Queen Maries days, when Churchmen had more cunning and could teach people many a trick.’”[x]

If all of this is just too unpalatable for the secular at heart, dump the milk and try the following recipe from Giovanni de Rosselli’s Epilario, or the Italian Banquet…, 1516. “To counterfeit butter,” grind 1 pound of blanched almonds with half a glass of rosewater, add a bit of sugar and, to make it yellow, some saffron. Let the mixture thicken over night and presto![xi]

Otherwise make your “cow cheese” even more delectable by following the recommendation in Hugh Plat’s Delights for Ladies to Adorn their Persons, Tables, Closets, and Distilleries, with Beauties, Banquets, Perfumes and Waters, 1603, which explains “How to make sundry sorts of most daintie Butter, having a lively taste of Sage, Cinamon [sic.], Nutmegs, Mace, etc.” Simply mix into your churned butter a few drops of oil extracted from one of the above listed herbs and spices. Delicious!

For my part, I’m going to slather some of the creamiest of butters on a slice of bread right now!

Ina Garten’s Recipe for Herb Butter

Ingredients:

1/2 pound (2 sticks) unsalted butter, at room temperature

1/4 teaspoon minced garlic

1 tablespoon minced scallions (white and green parts)

1 tablespoon minced fresh dill

1 tablespoon minced fresh flat-leaf parsley

1 teaspoon freshly squeezed lemon juice

1 teaspoon kosher salt

1/4 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

Directions:

Combine the butter, garlic, scallions, dill, parsley, lemon juice, salt and pepper in the bowl of an electric mixer fitted with a paddle attachment. Beat until mixed, but do not whip.

2012, Ina Garten, All Rights Reserved

http://www.foodnetwork.com/recipes/ina-garten/herb-butter-recipe.htm

Endnotes:

[i]http://www.mydairydiet.com/en/what-is-butter-and-curd/comparison-1-5-13

[ii] During the long medieval period, butter was a rarity in winter months when cattle had little to graze upon. The new shoots of spring led ultimately to the sweetest butter being churned in the month of May, as both Mikael Agricola (ca. 1510-1557) and Bartolomeo Scappi (ca. 1500-1577) observed.

[iii] Here, and throughout unless otherwise noted, I use the Holy Bible, revised version, Catholic Edition, 1952 translation for the Old Testament.

[iv] Bartolomeo Scappi, The Art and Craft of a Master Cook in Terence Scully, The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi (1570) (Toronto University Press, 2011), page 398.

[v] Pamela M. Simpson, “Butter Cows and Butter Buildings. A History of an Unconventional Sculptural Medium,” Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 41, no. 1 (2007), pages 1-20.

[vi] Simpson, “Butter Cows and Butter Buildings. A History of an Unconventional Sculptural Medium,” page 2, note 6.

[vii] Karal Ann Marling, “’She Brought Forth Butter in a Lordly Dish’: The Origins of Minnesota Butter Sculpture,” Minnesota History, vol. 50, no. 6 (1987), pages 218-228, specifically page 223.

[viii] Pliny, The Natural History, translated by John Bostock and H.T. Riley (London: Taylor and Francis, 1855), book 28, chapter 35.

[ix] Strabo, Geography, book 7, chapter 3. https://books.google.com/books?id=xjIzAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA454&lpg=PA454&dq=Strabo+%22capnobatae%22&source=bl&ots=h2pANDkj-W&sig=75vWElcxj-sItWzLPgHqBP25ml0&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi4o-yokOPRAhWO8oMKHSFqDKQQ6AEIIzAC#v=onepage&q=Strabo%20%22capnobatae%22&f=false

Accessed January 27, 2017.

[x] Iona and Peter Opie, The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), pages 124-125, rhyme no. 85.

[xi] Giovanni de Rosselli, Epilario, or the Italian Banquet Wherein is Shewed the Maner How to Dresse and Prepare all Kind of Flesh, Foules or Fishes. As Also How to Make Sauces, Tartes, Pies. With an Addition of Many Other Profitable and Necessary Things (London: William Barley, 1598), n.p.