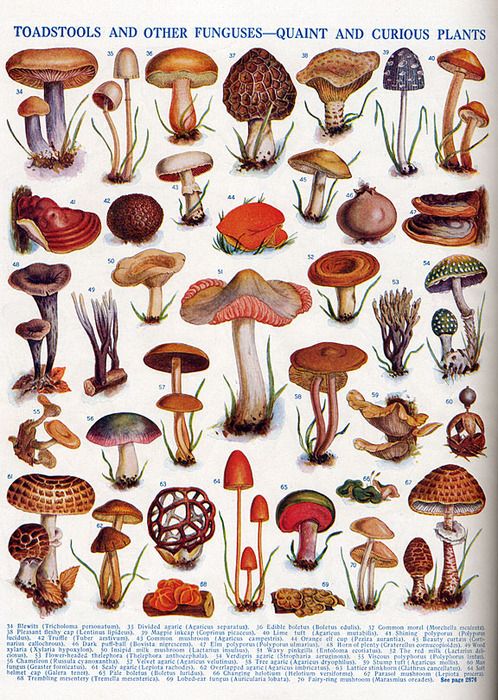

Delicate chanterelles, ruddy bright-capped russula, saffron milk cap lactarius deliciosus, and of course the wonderfully earthy boletus edulis, known to the French as cèpe, to the Germans as the Steinpliz, and to the Italians as funghi porcini. Mushrooms come in all sorts of shapes and colors – little white button caps, white-speckled red bulbs, orange-beige ruffled ribbons, blue and violet parasols… it’s amazing! There are about 750 species of genus russula, roughly 450 lactarius, and too many subspecies of the morchella genus to even count (in part because mycologists can’t agree on which funghi should be classed as such). Herein lies a problem. If mycologists are unsure about what counts as which type of fungus then what is the unlearned fungaiolo, or mushroom hunter, to do? This is not an idle question. [1] As tales of fungus intrigue make clear, eating mushrooms can be a risky business.

Writing in the first century Pliny the Elder duly noted that “among the things which it is rash to eat I would include mushrooms. Although they make for choice eating they have been brought into disrepute by a glaring instance of murder!”[2] Pliny, the first century cataloger of all natural thing who died in the miasmic air of Mt. Vesuvius in A.D. 79, was referring to the death of the Roman Emperor Claudius in October (prime mushroom hunting season) twenty-five years earlier. As Pliny – as well as Tacitus, Suetonius, Juvenal, and Josephus – tell the story, Claudius’s third wife, Agrippina the Younger, knew her mushrooms well. More to the point, she did not hesitate to use that knowledge to achieve a much-desired end. Like any doting mother, Agrippina wanted the best for her son, Nero (sired by Gn. Ahenobarbus). But that meant getting Claudius off the throne and putting Nero on it. Agrippina’s plan was simple and effective. One day between the sixth and seventh hour, Agrippina joined Claudius to enjoy the antics of a troupe of comic actors. As they watched, the imperial couple munched on mushrooms. With a show of affection and taking care with each selection, Agrippina alternately popped a delicate field mushroom first into the mouth of the portly Claudius and then into her own. Within hours, the Emperor was dead, Nero assumed the throne, and rumors went wild. Was the mushroom itself poisonous or simply the vehicle for the delivery of some other toxin? In either case, it is worth keeping in mind Pliny’s advice to those who feel compelled to indulge then do so only when snakes hibernate. Apparently, the delicacy of mushrooms makes them particularly susceptible to absorbing whatever is wafting in the air and this includes the poisonous “breath” of any serpent slithering past.[3]

buying mushrooms in Barcelona

The ill effects of ingesting the wrong sort of mushroom is by no means limited to antiquity. According to Voltaire, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI suffered Claudius’s fate in October 1740.[4] Emperors were not alone in being fed toxic funghi. On multiple occasions the Madonna dell’ Arco, whose shrine is on the outskirts of Naples, was credited with saving the life of someone who mistakenly ate the wrong sort of mushroom. Take the case of “Giovanni Andrea and Rebecca di Martino, both having eaten poisonous mushrooms, were near death” when they prayed to the Madonna, who beneficently restored them to good health.[5] The many accounts of poisoning-by-mushroom may very well explain Alessandro Petronio’s denunciation of the mushroom as the “excrement” of the earth! In a chapter devoted to “fonghi” in Del viver delli Romani et di conserver la sanità, Petronio, who was the pope’s private physician, claimed mushrooms “suffocate” the breath, cause stupor, and trigger apoplexia, which, claimed Voltaire, is what felled Charles VI![6]

Buying mushrooms in Richmond, Virginia

With all of these dangers in mind, cooks and botanist composed lists of “safe” mushrooms and prescribed methods of preparation to ensure safety.[7] The eminent maestro Martino of Como instructed the readers of his cookbook, circa 1465, to first clean mushrooms then boil them in water seasoned with garlic and bread before frying![8] Bartolomeo Scappi offered more recipes in The Art and Craft of the Master Cook, 1570. To prepare a thick soup of salted mushrooms, soak the mushrooms for at least eight hours, changing the water repeatedly. Once the saltiness is gone, chop the mushrooms and sauté in olive oil flavored with spring onion, pepper, cinnamon, and saffron.[9] To be honest, it would be a lot easier to simply pair mushrooms with a hearty serving of pears. For well over a millennium, pears were considered a natural antidote to fungus toxins. Hence, “Pyra sunt theriaca fungorum!”[10]

But historical assessments of mushrooms are not all couched in warnings and disparagements. Aztec prostitutes reportedly kept mushrooms on hand for their clients.[11] An explanation for this practice may be found in a directive King George IV (1762-1830) issued to his ministers in foreign courts. It concerns the most prized of funghi, the truffle. George’s ministers in Turin, Naples, and Florence were “instructed to forward by state messenger to the Royal kitchen any of those funghi that might be found superior in size, delicacy or flavor… it being a positive aphrodisiac which disposes men to be exacting and women complying.”[12]

Given this wondrous – and decidedly checkered history – it is not at all surprising that Alice stumbled upon mushrooms in Wonderland. Having grown quite small – a mere three inches in height, Alice encounters the Caterpillar lounging atop a mushroom. As he puffs his hookah he quizzes her. “What size do you want to be?” asks the Caterpillar. A bit bigger would be nice, Alice responds. And with that “the Caterpillar took the hookah out of its mouth and yawned once or twice, and shook itself. Then it got down off the mushroom, and crawled away in the grass, merely remarking as it went ‘One side will make you grow taller, and the other side will make you grow shorter.’ ‘One side of WHAT? The other side of WHAT?’ thought Alice. ‘Of the mushroom said the Caterpillar… and in another moment it was out of sight.”[13]

… and here’s a lovely recipe from Angie’s Southern Kitchen:

Wild Mushroom Tart

Pie Crust click here for pie crust recipe

Filling

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 tablespoon butter ~ additional to butter pans

2 medium shallots finely chopped

1 garlic clove minced

1/2 pound Cremini mushroom thinly sliced

1 pound assorted wild mushrooms thinly sliced ~ I used shiitake, oyster + more creminis

1 teaspoon fresh thyme leaves

1 teaspoon salt

fresh ground pepper

1/4 cup mascarpone cheese at room temperature

1/4 cup whole milk

2 large eggs

1/2 cup grated fontina cheese

1/4 cup grated parmesan cheese

Preheat oven to 375. I made my crust and put it in the tart shell pans with removable bottoms. The size shown is a 6 inch tart pan and it made 4 of them. I buttered them really well. After I had the pie crust in the shell, I placed all on a baking sheet. Then made the filling. I saute my shallots in the oil and butter until tender. Then added the garlic for just a second then mushrooms and thyme. I saute mushrooms until almost all moisture was gone. I let the mushrooms cool and then added them to a bowl. Then add the remaining ingredients to the bowl the salt, pepper, mascarpone cheese, milk, eggs, fontina and parmesan cheeses. Once this is mixed well add it to the prepared pie shells. Do not over fill. I baked mine for 20 minutes and they came out nice and golden brown and the crust was wonderful nice and crunchy on the bottom. We all love it! Great recipe….I just love it when I find a good one!! Thanks Smitten Kitchen!

http://www.angiessouthernkitchen.com/2013/01/wild-mushroom-tart/

And for good measure: my lobster raviolo topped with truffle

[1] Of course, one can always turn to A.M.I.N.T. (Associazione Micologica Italiana Naturalistica Telematica), which catalogues about 1,200 types of mushrooms. http://www.amint.it/ You will need to register and pay a nominal fee.

[2] Pliny, Natural History, book 22, chapter 46, 92-93. Also see V.J. Marmion, “The Death of Claudius,” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine (May 2002),, vol. 9 (5), 260-261.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1279685/

[3] Pliny, Natural History, book 22, chapter 48, 100.

[4] “Charles the Sixth died, in the month of October, 1740, of an indigestion, occasioned by eating champignons, which brought on an apoplexy, and this plate of champignons changed the destiny of Europe.” Voltaire, Memoirs of the Life of Voltaire (London: G. Robinson, 1784), pages 48–49.

[5] Michele Miele, Le origini della Madonna dell’ Arco. Il “Compendio dell’historia, miracoli e gratie” di Arcangelo Domenici (1608) (Naples-Bari: Editrice Domenicana Italiana, 1995), page 175, miracle no. #126.

[6] Alessandro Petronio, Del viver delli Romani et di conserver la sanità [1581], trans. M. Basilio Paravicino (Rome: Domenico Basa, 1592), 136. Apoplexy is difficult to define during that period but seems related to stroke.

[7] In his treatise The Fruit, Herbs, and Vegetables of Italy, Giacomo Castelvetro (1546-1616) names 8 types off edible mushrooms but also references “a huge variety… whose names do not come immediately to mind.”

Among the named, are: Field mushrooms –“ small, very white and “not a bit harmful”; Ovali – egg-shaped. “Although considered some of the best, and quite good, it is better all the same to be on the safe side, and boil them” before consuming a bowl full; Parasol mushrooms – eat only those that have “a ring in the middle of the stalk,” a true sign that they are safe for human consumption; Boletus or porcini – “They are highly esteemed, whether eaten fresh or salted”; Polmoneschi- in addition to eating them, “we use them [when dried] in Italy to light the fire on winter nights.”

Roman mushrooms, which the local population refers to as ‘fongaruola,’ are “buried in a terracotta pot filled with the best garden soil and watered every morning.” The yield is impressive. A single pot “will produce 15 or 20 mushrooms by the next morning.” In Rome “many fine lords and cardinals have pots of them on their windowsills.” See Giacomo Castelvetro, The Fruit, Herbs & Vegetables of Italy (1614), trans. Gillian Riley (Totnes, Devon: Prospect Books, 2012), pages 99-103.

[8] Martino of Como, The Art of Cooking. The First Modern Cookery Book, ed. Luigi Ballarini, trans. Jeremy Parzen (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2005), page 68.

[9] Terence Scully, trans., The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi (1570). L’arte et prudenza d’un maestro cuoco (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008), page 362, recipe no. #235.

[10] Ken Alba, Eating Right in the Renaissance (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2002), page 254 and 259. The quote Pyra sunt theriaca fungorum comes from Prosper Calanius, Traicté pour l’entrenement de santé, 1533.

[11] . Jan G. R. Elferink, “Aphrodisiac Use in Pre-Columbian Aztec and Inca Cultures,” Journal of the History of Sexuality, vol. 9 (2002), 1-2.

[12] John Davenport, Aphrodisiacs and Anti-Aphrodisiacs, circa 1869, as quoted inMiriam Hospodar, “Aphrodisiac Foods: Bringing Heaven to Earth,” Gastronomica, vol. 4 (2004), page 90.

[13] Excerpt from the 5th chapter, “Advice from a Caterpillar,” of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, 1865.